One for the ages!

Here’s some unexpectedly good news: life expectancy in Australia has increased to an all-time high (hurrah!).

Life expectancy at birth has increased to 80.4 years for males and an even higher 84.5 years for females.

A decade ago life expectancy was lower by 1.9 years for males and 1.2 years for females, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

The increase in life expectancy at birth reflects declining death rates at most ages, while “for both men and women, Australia has a higher life expectancy than similar countries such as Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the USA” noted the ABS.

Life expectancy is quite similar across the states, except for being markedly lower in the Northern Territory.

This is potentially jolly nice news, provided you have a decent pension plan that is.

‘J curve’

One of the challenges of an ageing population is the dependency ratio, which is no doubt one of the reasons why Australia runs a high immigration programme targeted at bringing in young workers and international students across a range of visa categories.

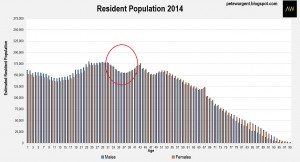

When looking at an estimated resident population pyramid flipped on its side, it’s interesting to note that with immigration of international students and younger migrants having been ramped up significantly, there is relative dearth of Australians in their thirties right now.

This is one contributory factor to the percentage of homes being bought by first homebuyers tracking at a lower share than was previously the case, combined with the surge in investment property purchases, (particularly with interest rates having been slashed since 2012).

In fact, the population pyramid presents a relatively weak proposition for Australia’s housing market at present, with the chart above showing only 2.6 million persons in the 31 to 38 age bracket (what I believe will be a key homebuying demographic in the major capital cities).

That said, with annual population growth much rising to a considerably stronger level since 2004, hundreds of thousands of new young migrants will move in to that key homebuying age bracket eventually, it will just take time.

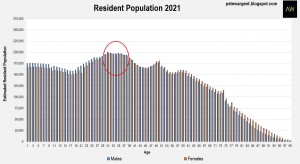

By 2021, in fact there will be well over half a million more persons in that cohort – about 534,000 or so.

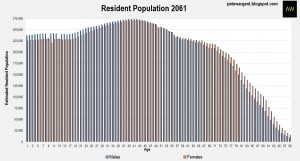

Over time Australia’s immigration programme is projected to keep the dependency ratio at a workable level.

Although there will inevitably be more older Australians over the retirement age thanks to life expectancies having increased across the board, there will also be be many millions more working age residents to support the economy and the tax take.

Correction!

There are a couple of reasons why I think the endlessly talked-about housing correction and possibly ensuing (gasp!) recession in Australia might be a relatively short-lived affair.

The first reason is related to the shape of the population pyramid above.

Never underestimate the will of the Australian political class of both persuasions to combat falling house prices!

These charts show that there will in time be hundreds of thousands of potential targets for the inevitable resurrection of the first homeowners grant.

The second reason is that unlike some of the worst-affected countries through the financial crisis, Australia runs an open economic model, with a floating exchange rate since 1983.

The choice of exchange rate regime is extremely influential in the preserving of economic stability and the way in which the economy can deal with external shocks.

Recall how fast and far the dollar fell in 2008 from 98.5 US cents in July to well below 65 cents before the calendar year was out.

I wouldn’t like to put a number on it, but in the event a major housing market shock the exchange rate would presumably be heading lower than that, and possibly a lot lower – recall that we have already previously been below 50 US cents this side of the Sydney Olympics.

The lower dollar can be one stabilising factor, combined with interest rates being slashed to the zero lower bound and a thunderous burst of fiscal stimulus (thankfully we have relatively low public debt in Australia).

Yes, bank funding costs might rise, although the major banks’ funding composition is largely accounted for by domestic deposits plus equity these days.

As for the health of Australia’s banks, they have massive exposure to the domestic residential housing markets, but the Reserve Bank’s vast ~$350 billion Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF) is in effect a monster line of credit designed to ensure that insolvency cannot be induced through illiquidity.

This is largely conjecture, I’ll just note here that some housing markets are at greater risk than others!

No comments:

Post a Comment