Many years ago, my wife and I went to dinner with another couple whom I’ll call Pam and Stan.

I went to high school with Pam, and my wife had grown up knowing Stan.

They were among the smartest and most successful people we knew.

I was always a bit intimidated by them and their lives.

I remember this particular conversation well because Pam made a comment that has stuck with me ever since.

Pam drove a well-used minivan.

During our conversation, she mentioned wanting a new car, but then said, “We can’t afford it right now. It’s just not in the budget.”

At the time, I didn’t know many successful people who would say out loud, “We can’t afford it.”

After all, what did she mean they couldn’t afford a new car?

Pam didn’t go into specifics, but the discussion suggested a simple reason. They didn’t buy a new car because they had a budget.

That budget represented their best effort to align their current spending with what they really wanted in the future. Based on this calculation, they couldn’t afford a new car.

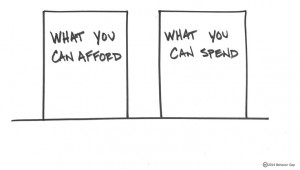

It seems like such a simple reason, based on obvious logic. But Pam’s definition of “afford” isn’t all that common anymore.

Before credit became so readily available (and socially acceptable) we defined “afford” as being able to pay for something.

It meant that if we didn’t have the money, we didn’t buy the stuff.

Over time, the rare exception of borrowing money to “afford” something became more and more common.

For example, people went from buying their first home only if they had the cash on hand to buying it by taking out a mortgage.

It changed the equation and reframed what we meant by “afford.”

It was no longer about having all the money, but whether we could afford the loan payment.

Fast-forward to today, and the question of what we can afford has fully taken on that new meaning.

If we can afford the payment, or at least hope we can, we buy the stuff.

We rarely bother to look at the big number.

If we can afford the payment, or at least hope we can, we buy the stuff

Operating this way is madness.

While home mortgage rates are relatively reasonable right now, we usually finance other spending with more expensive credit.

It’s financially senseless and an all-but-guaranteed path to emotional pain.

Most of us understand this simple math.

If we don’t have the money, we don’t buy the 60-inch flat screen, even if it’s on sale.

But while the numbers are obvious, the emotions are less so.

When everyone around us is playing the game, it seems difficult to avoid.

Your neighbors all have that TV.

They all have newer cars.

They all go on cool vacations.

Spending money doesn’t appear to be a problem for them.

So, we tell ourselves, if they can afford it, certainly we can too.

Before we know it, we’re hitting that one-click, buy-now button whenever the mood strikes because we can “afford” it.

We need to get better at looking past both the monthly payment and the total price.

What we can afford doesn’t just depend on the amount of money sitting in the bank.

We may have $1,000 handy, and there may be an amazing offer on some new toy we really want.

But we can only afford to buy it if that $1,000 doesn’t belong somewhere else, say to a debt that you still owe.

What we can afford doesn’t just depend on the amount of money sitting in the bank

What we can afford needs to be put in context.

And the better, albeit more difficult, way to do so is the way I heard Pam explain it years ago.

She took the time to work through the trade-offs.

She understood that by saying “no” to the new car, she got to say a much bigger “yes” to the goals she built into her budget.

It’s only then that we can know whether we can really afford something after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment